The Mississippi River is going to hell: How fast can the tides turn? The Coast Guard says it’s working towards a safe, restricted one-way flow

It’s crazy to think the Mississippi River could end up overflowing its banks when just last fall, parts of the river were at record low levels. How quickly the tables can turn.

There are more than 200 vessels and over 2,253 barges waiting in line to get through two sections of the river where traffic has been halted due to flooding. The Coast Guard could not say for certain when traffic might resume, but it said that it hopes to do so by Friday.

“The Coast Guard, [Army Corps of Engineers] and river industry partners are working towards the goal of opening the waterway to restricted one-way traffic when it has been determined safe to do so,” said the Coast Guard’s statement.

Even when barges start moving once again, they’ll have to carry as little cargo as possible in order to not ride too deep in the water. Rather than a single vessel moving between 30 to 40 barges at once, they’ve been forced to move no more than 25 barges on each trip due to the more narrow channels.

This is just one more stumbling block for US supply chains that are still struggling to recover from disruptions since the start of the pandemic two and a half years ago. Most of the nation’s imports arrive by container ship, but West Coast ports are still congested.

And while a freight railroad strike was narrowly averted last month, even the freight railroads themselves admit they are providing substandard levels of service as they struggle with their own labor shortages.

Twenty-five years of rainfall on the Mississippi River: State of the art and status of the situation in the western United States during the recent drought

Prolonged drought in the western United States has taken the reservoirs in the Colorado River basin to historically low levels. The water supply is important for both the power of hydropower and for the water needed by western states.

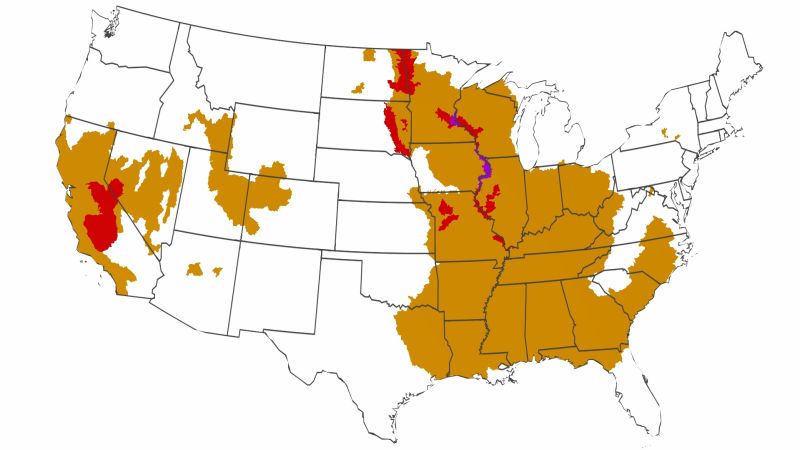

Findings show that the eastern half of the U.S. is getting far wetter on average, with some areas – including parts of the Mississippi River basin – now receiving up to 8 more inches of rain each year than 50 years ago.

On the left and right you can see imagery taken on the Mississippi River in Memphis, Tennessee, in March, 2022, and again in October, 2022. The images are natural color images – processed to resemble the actual color of the Earth — taken by the Sentinel-2 satellite.

A University of Missouri weather station in Columbia, for example, reported just 6.46 inches of rain between June 2 and September 27, the Drought Monitor noted. That is more than 11 inches below normal and the driest period in over two decades.

The US Army Corps of Engineers has begun work on a 1,500-foot-wide underwater levee in the Mississippi River to help prevent saltwater from pushing up the river.

The corps announced last week it would dredge sediment from the bottom of the river and pile it up near Myrtle Grove, Louisiana, to create what’s known as a sill, which will act as a dam for the denser saltwater in the lower levels of the river.

“When it falls below 300,000 cubic feet per second, it doesn’t have enough force to keep the saltwater at bay,” Boyett said. The flow rate north of the planned bridge has been low for over a week according to the US Geological Survey.

Boyett said the problem typically resolves itself once there’s enough rainfall upstream to ease the drought. He said that what’s occurring right now is similar to the 2012 low flow.

Boyett explained that the difference is that after Hurricane Isaac dropped 20 inches of rain in some places, it changed the flow on us. “In this case, we’re looking at an area where it’s really not enough rain in the current forecast to change it.”

As the water level in the Mississippi River drops, saltwater intrusion is already impacting a water treatment plant in Boothville in Louisiana’s Plaquemines Parish, and is projected to reach another one in Pointe a la Hache. Both of those locations are downriver from the planned sill.

“When you’re looking at the areas below the Belle Chase, the smaller water intakes that Plaquemines is using, the parish kind of has the responsibility for mitigating for that saltwater because it is a natural phenomenon,” Boyett said.

The sea level rise expert with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration said it would be difficult to prevent saltwater from reaching New Orleans, even though the corps thinks it will be successful.

Climate and environmental pressures such as sea level rise, land subsidence and the deeper of the channel are all threatening the Mississippi River Delta. Sweet believes that creating sills will only cost more in the future if there isn’t a permanent fix.

This is a heavily fortified area with a lot of engineering and we now have levees on land to protect against flooding.

It is not known how river communities will look a century from now. But most experts agree: Change is necessary to create a better and safer future. Levees and floodwalls alone aren’t working anymore. Communities will need to make space for the water as the flood risk increases. And the time to act is now, instead of waiting for the next flood.

The increased likelihood of major spring flooding in the Upper Mississippi River Basin could be due to the rapid snow melt.

The Pecatonica River flooded the basement of Laurie Thomas’ family home after it jumped its banks.

The last few years have seen a number of major floods in Freeport. Thomas and her mother have experienced flooding at least 15 times in the past 20 years.

St. Louis broke a century-old rain record this summer. In Jackson, the main water treatment facility was overwhelmed by the rain. Historic flooding left eastern Kentucky communities decimated and searching for protection against climate change.

U.S. infrastructure wasn’t designed for this climate-fueled extreme weather. It’s causing economic strain, impacting quality of life, and forcing people to make hard decisions about whether to stay or leave.

The Mississippi River River Basin Adapts as Climate Change Bring: Lessons for River Communities, Homes, and Communities in Freeport, MS

Last year, the city of Freeport, with over $3 million from the Federal Emergency Management Agency, launched a program to buy and remove homes along the river and return the land to floodplains. The value of the average home on the east side is around $15,000, according to city officials. $31,000 can be offered to homeowners.

Thomas says that’s just not enough money for her mother to pick up and start over elsewhere. She, and some neighbors, would rather take their chances with the river.

The Pecatonica River has always been a home to people, but lately the floods have been worse. “But they’ve been worse everywhere else too. That’s not a reason to evict people from their homes.

Changing river communities like Freeport will happen regardless of whether or not you buyout or not. But for these efforts to succeed, they’ll need support and substantial resources. Thomas’ families will continue to opt out completely if that isn’t possible.

Climatecentral was asked by the Mississippi River Basin Ag & Water Desk to analyze 50 years of rainfall patterns using data from the National Weather Service.

Climate change models show that more increases are likely in coming years, according to Climate Central data scientist Jen Brady.

And when it rains, it pours, based on rainfall intensity data. According to the Climate Central analysis, there has been an increase in the average yearly rainfall in parts of the basin.

Pat Guinan, a professor at University of Missouri, says that the heat is the main cause of the trend. As greenhouse gasses from fossil fuels heat the Earth, that warming extends to the oceans and the Gulf of Mexico — a primary source of the atmospheric moisture for the Eastern U.S. Warming oceans produce more water vapor, and a warming atmosphere can hold more moisture, which can then deliver more precipitation in short windows of time.

Guinan said recent decades have given rise to a stark divide seen across the continental U.S., with the western half of the country becoming increasingly arid and prone to drought, while the eastern half is faced with exceptional moisture, often delivered in bursts.

Source: https://www.npr.org/2022/10/18/1127966940/mississippi-river-basin-adapts-as-climate-change-brings-extreme-rain-and-floodin

Atchison County, Mo., a floodplain adapts as climate change as extreme rain and flood induced more than 10,000 acres of flora and fauna

The western border of Atchison County, Mo., follows the twisting path of the Missouri River, which is part of the Mississippi River Basin. Acres of corn and soy fields once lined its shores, but after a nearby levee suffered seven breaches in the Flood of 2019, the cropland was ruined.

Instead of rebuilding the levee and replanting the crops, Atchison County let the floodplain be a floodplain. The levee board proposed moving one of the levees and restoring the area to its pre-recession state. Knee-high prairie grass now covers the open space, providing a greener, more sustainable form of flood control.

“The old way isn’t working for today’s population. The change of solution has resulted in a new look at the role nature can play, according to Laura Lightbody, the project director of the Flood-prepareded Communities project.

Research has found that these solutions successfully mitigate flooding. Proactive buyouts provide permanent solutions for communities in harm’s way. When paired with those buyouts, levee setbacks reduced flood risks in every studied scenario in the Mississippi River. The increased flora and fauna of the floodplains offer opportunities for recreational activities.

Source: https://www.npr.org/2022/10/18/1127966940/mississippi-river-basin-adapts-as-climate-change-brings-extreme-rain-and-floodin

The Mississippi River Basin Ag and Water Desk: Why the Federal Government isn’t Providing the Support It Needs to Respond to Hurricanes

“There’s more and more research that’s making it more compelling…and it’s often less costly,” Lightbody said. I think that’s why we’re seeing more of it.

Congress has slowly begun to direct agencies to craft programs that offer communities more support. In 2020, the FBI launched the BRIC program, which provides funding to fortify areas before disasters strike. This October, FEMA will have $2.3 billion for such projects — a windfall compared to past years, but still a fraction of the $460 billion spent on disaster response between 2005 and 2019.

Headwaters Economics said that inland Mississippi River communities have received a smaller percentage of Bric dollars than coastal states.

The money could be more easily accessed in small towns like the one in the river basin, according to Eric Letvin.

But Pew’s Lightbody says communities need to come up with local solutions as well. She thinks that the federal government doesn’t have enough money.

Bryce Gray (St. Louis Post-Dispatch), Connor Giffin (Louisville Courier Journal), Halle Parker (WWNO-New Orleans Public Radio) and Brittney J. Miller (The Gazette of Cedar Rapids) contributed reporting. This story was adapted from a series by the Mississippi River Basin Ag & Water Desk, which is based at the University of Missouri, in partnership with Report for America and the Society of Environmental Journalists, funded by the Walton Family Foundation.

Editor’s Note: A version of this article originally appeared in the weekly weather newsletter, the CNN Weather Brief, which is released every Monday. You can sign up here to receive them every week and during significant storms.

Minneapolis, Minnesota, is experiencing its eighth snowiest season on record, and it’s going to get worse every year, according to the North Central River Forecast Center

Minneapolis is experiencing its eighth-snowiest season on record, with 81 inches of snow, compared to its average of 51 inches. Bismarck, North Dakota and Grand Rapids, Michigan, are experiencing their third-snowiest season; Duluth, Minnesota, is coming in at sixth; and Sioux Falls, South Dakota, is eighth.

The region has an above-average snowpack and is very wet, according to the North Central River Forecast Center.

“The snow water equivalent in the snowpack that’s still on the ground is in the top 10 or 20% compared to historic years, so there’s really just quite a lot of snow water out there,” Hoy said in a media briefing. It has not had a chance to melt out quickly because of the colder temperatures.

While temperatures may get above freezing during the day across parts of the Midwest, for the most part, lows are returning below freezing, which has kept the snowpack from rapidly melting until now.

“If we were to get consistency of warm, high temperatures, right around our normal highs or where they’re at right now, that would give us a much more rapid snow melt, and increase that flooding potential,” explained Ryan Dun.

If a major flood does materialize in the coming weeks and months, cities like Davenport, Iowa, will be at risk. Davenport has been watching the situation closely and is prepared for what to come, according to the Mayor.

The pumps are tested after they have been set up. When we think a flood is coming, we practice the work. The barriers for the flood are pre-staged downtown before being set up. Notices are sent to potential impacts of businesses and residents. They are aware of what goes on. We are of course watching it.

Just four years ago, a temporary levee broke due to rapid melting snow and rain, causing flooding along the Mississippi River, but that’s the only event that has stopped Matson from being the mayor.

Many people are familiar with the topic and some of our old-timers have dealt with it a long time. We have people that live along the river and when the flood comes, they boat in and out,” Matson said.